A pandemic love story

This short story was first published in Brittle Star Literary Magazine (United Kingdom), Issue 46. Support new writers, and buy a copy here.

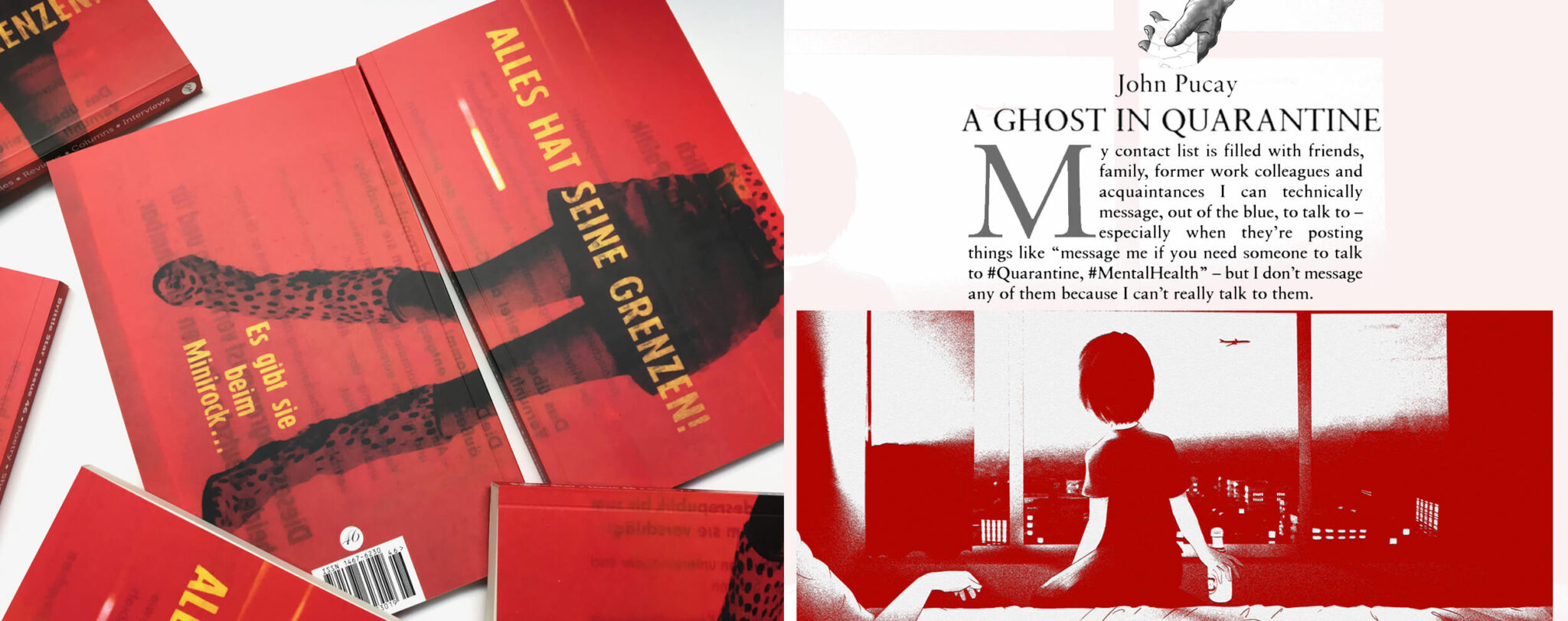

My contact list is filled with friends, family, former work colleagues, and acquaintances who are posting things like, “message me if you need someone to talk to #Quarantine, #MentalHealth” on social media—but I don’t message any of them because I can’t really talk to them.

I stare at the names of people I’m supposedly close to.

I dial my close friend and gaming pal, Gabriel.

I call him because I needed to talk about my girlfriend (my ex, by now); who vanished from my life, without warning, for no apparent reason, just as the city was banning alcohol—the universal salve for broken hearts—to discourage incognito social gatherings. Five minutes into the call, he starts disparaging my ex on my behalf (maybe to make me feel better). It doesn’t make me feel better, so I talk about him instead. For the next hour and fifty-five minutes, he tells me about the pain of shutting down his newly opened salon business, because of the pandemic. Then he wraps it up with a “really sorry about the breakup, bro”, on the two-hour mark.

Our conversations weren’t always one-sided. But I can understand his frustration. It’s his first brick-and-mortar business. I’ve seen how much blood, sweat, and cash he spent, putting it up. My heartbreak was just really bad timing.

Then there’s my other close friend and reading buddy, Eliza. She used to be a model, my first portrait subject. She just moved in with her politician husband. She tells me about this new cream she bought, to cover up the eye bags caused by her new-born baby. She says she wished her in-laws didn’t visit them when the Lockdown happened.

Several months ago, I sent her a book that I knew she would love—but she hasn’t read it yet. She doesn’t really have the time these days, she says. Just before I could bring up my ex-girlfriend, I heard the bawling of an infant in the background.

I try talking to other close friends on the list.

I tell them about my pain and the deafening silence of my lonely apartment. I confess, to a handful few, about the stack of pillows that I set up every night: How I lean on them into a half-sitting position when I sleep, because my heavy chest couldn’t breathe otherwise.

They listen and tell me it’s going to be alright. Because what else can they say? The love of my life ghosted me and there’s nothing I (or they) can do about it.

They offer passing, virtual hugs that are light and quick to move forward. Even under social isolation, life goes on and work must be done.

Others try harder—bless their kind heart—by embracing me (still virtually, of course) as tight as they can. It lacks the warmth of genuine empathy, but I appreciate the effort.

It doesn’t make me feel connected, though.

The world is like a huge jigsaw puzzle, made up of different pictures and sets. I’m a puzzle piece, in a heap with other pieces. I am not alone. In fact, I am surrounded by millions—even billions—of virtual and physical puzzle parts. But my loops and sockets do not fit any other piece. I cannot join. All around me; individuals, pairs, and groups are locking onto one another, creating full and partial pictures, while I am left NOT alone but also NOT connected with anyone.

Every day, I stir from my half-sitting sleep, take a shower, brush my teeth, and nibble on a rationed portion from my food stock. My new employer is holding off work (we have enough WFH employees atm, he chatted), so I spend the time budgeting my depleted savings, working out an hour or two a day, and exchanging mundane memes and hollow anya ngays with Zoom buddies and Facebook friends. Every now and then, I call my parents to listen to their views about President Rodrigo Duterte’s latest press release.

Then one morning, as the last cool winds of summer whiff past my room, I find her there: sitting on my floor, facing the window, just a few feet from my bed. I get up and the bed creaks and she jerks her head around to look at me—like how she always does when I suddenly call out to her. I almost forgot about that mannerism. Or maybe I’m half-dreaming, and she is just a projection of my vivid memories.

She quietly asks if she woke me up and I say no, I woke up on my own. She nods and smiles that smile I remember so well.

All of a sudden, I feel a rumbling inside me: questions, sharp as daggers, screamed to be thrown. They reverberate in my heart and shoot up my throat, so I swallow hard to keep them from firing violently out of my lips.

I take a deep breath. I miss you, I whisper instead. It’s all that matters, really.

I miss you so much, I say, as the first rays of sunlight glint through the corners of my eyes, streaming down my cheeks.

Me too, she says. She never was very vocal with her feelings. Maybe it’s her culture and upbringing. Maybe that’s just how she is.

I’m on her bed. We’re in her condo rental, sprawled on the mattress together, a month away from her flight home. Her head is lying on my chest and our hands clasp tightly, fingers interlocking like a pair of perfectly fitted jigsaw puzzle pieces. I really like you… more than you think, she confesses. Unlike my American employer who is quick with a “perfect” or “love”; she rarely uses strong words. That’s just how she is; simple words, heavy meanings. I look at her and think of asking: then why did you leave me without saying a word? But I don’t.

I’m sitting atop a breakwater. We’re in Manila Bay, watching the “best sunset view in the world”. Her head is leaning on my shoulder. She says my name and I look at her. I will really miss this place, she says. Won’t you miss me too, I tease. Of course, that automatically includes you, she says. You should already know that, she adds, with a hint of a blush. I want to ask her: Am I also supposed to just know your reasons? But I don’t.

I’m in a hotel, near the airport. It’s our last night together. We pack her things and decide that, though the distance is tough, we will be tougher. We decide to bet on each other’s heavily meaningful “like”. I want to ask her: What suddenly changed? Is it something I did or said? Something I didn’t do or failed to say? Is it somebody else? But I don’t.

I’m in a cafe, late at night, three weeks before the government closes all cafes. We’re eating dessert together through a Line video call. She asks where I am, so I pan the camera around. It takes her a moment, but she recognizes the place: the cafe where we first met. She says she misses my city and my country very much. I smile knowingly at her, and she laughs. Okay, I miss you too, she relents. I cup my ears and ask her to say it again. I didn’t quite hear it, I tease and she laughs some more, covering the camera with her hands. I won’t repeat it, she exclaims. After a while, she shows me her laptop. She has been searching, she says. I look closely and see a budget airline’s website displaying a list of flights going to my country, to my city — to me. After two months on the new job, she says she will have enough cash and leave credits to visit me soon.

I surmise that my visa application will probably get denied, since I don’t have enough “show money” in my bank. So I tell her I’ll be waiting. I tell her she only needs to worry about her flight ticket (she doesn’t need a visa to visit my country) and I’ll take care of the rest. But I don’t tell her about the dream project that I declined.

I don’t tell her that I took a higher paying job, over my much-anticipated dream project, so I can eventually afford the “show money”. I just don’t. I can’t. I never had the chance.

The unsaid words and the unasked questions bounce violently inside my head, like rubber balls smashing against the walls of my skull. The “Enhanced Community Quarantine” announcements grate painfully against my ears.

Back in my apartment, I get up from bed, take a shower, brush my teeth, and then stand in front of her.

I think about the messages and the voice mail I’ve sent over the past few days; the asking, the pleading, the begging—all unopened and ignored. I think about her “Active Today” status on messaging apps; proof that she is alive and well, living thousands of miles away from me, and thinking thoughts that I probably don’t even occupy.

Thoughts, feelings, and dreams—a whole picture that I’m not a part of.

Then I open my phone, exit the contact list, swipe on the music app and scroll to a song by Bill Withers; the one about leaning on someone. The words that were never said, the questions that were never asked and the deafening silence that permeate my solitary apartment fade away; like background noise gradually muted by the song’s warm humming.

I take her hand and lead her to the modest space in my living room.

And then we dance.

Music: Lean on me — Bill Withers