Salary and Time

I knew I wasn’t living my life well. But the full realization came during a chance meeting with old friends, one Saturday afternoon. Meeting old friends is like bumping into your past self, some parts good and some bad, obscured by age and forgotten with time and new habits. They remind you of the dreams, convictions, and passions of your younger days.

A lunch and a quick dinner later, I peer at the drizzle-filled city alone, through a commuter jeepney’s window. I sat there, mulling over our conversations, amazed at what I have lost without even noticing.

At the end of my sophomore year, my university changed its academic calendar, which resulted in four months without classes. I needed a DSLR camera for my media course, so I applied to and got accepted at a call center that paid above-minimum rates to unskilled undergrads like myself.

I bought my first camera in two months, became “regularized” on the third, and snagged a decent laptop, for video editing, on the fourth. The original plan was to resign after buying basic filmmaking equipment. But as my mom says, the only sure plans are insurance plans (and if you need life insurance, please take one or two from my mom).

Being poor enough to be officially categorized as “Indigent,” (third-world-country indigent) I was reluctant to return to broke-ness. It was a boring, soulless job, but it paid. The taste of adult money weighed deliciously in my brand new jeans’ pockets. Pay is like a pack of addicting chips: You always need to take just one more.

My junior year rolled in, and the job stayed. My government scholarship required a full class load, so I scheduled my classes outside work hours and quit the university clubs I used to be very active with.

I followed a ritual at work. I would arrive an hour or so before my graveyard shift, drape my jacket on the cubicle chair, prep my headset, refill my water tumbler, and set up my workstation: Turn on the PC, connect the headset to the phones, login, sip some warm water. Then I go outside, buy coffee from the smoking area’s vending machine, and enjoy the fresh, evening breeze.

During these moments, I found myself thinking, “I’m okay.”

In the comfort of a regular job, I could imagine my life as an office worker: Work my nine-to-five (or 10 pm to 6 am, in my case), anticipate breaks and log-outs, wish that tomorrow is my day-off, travel to some beach or overseas city for vacation, apply for loans, build a sizeable credit score over years of tenure—become a typical, office employee.

That word reverberated throughout my being. Employee. It reeked of security and stability—something we, the poor, always struggle to find. Employeehood offered a safe, respectable, super okay life.

But I’m not happy with “okay.” I’m not happy that 9 hours of my day, 5 days a week, is spent on something I would never do unless I’m paid to do it. 9 hours of work, 8 hours of sleep, and 3-4 hours of commute, work preparations, and meals. 22 hours of a day, gone. 92 percent of my life burned on a cycle of sleeping, preparing, and commuting to chase money, and then chasing money.

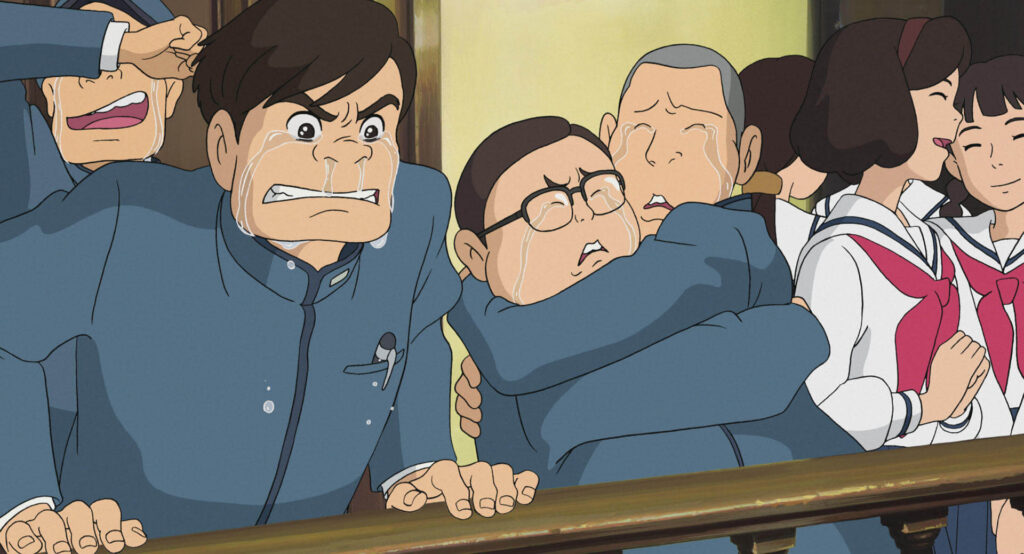

Studio Ghibli’s From Up on Poppy Hill tells the story of a group of high schoolers in the 1960s, at the peak of Japanese student activism, banding together to stop their school administrators from demolishing their decrepit—but passionately used—Latin Quarter.

To me, that film embodies the picture of a fully-lived youth: Optimism, idealism, passion, energy, and teenage ardor. If the characters were in college, I’m sure bouts of excessive drinking and sex would be included.

Fortunately, my old friends and I, in our university clubs, were living that ideal picture during the last semester of my sophomore year. Our Catholic university, the biggest university north of the country, was rotting in the dark ages and we, the student leaders with big ideas and enormous confidence, were going set it ablaze in the flame of progress. It was the most passionate time in my college life. We planned and schemed and made speeches and drank and sexed aplenty. We were changing things. We were revolutionaries (or at least we felt and thought we were).

Then the academic calendar shifted. I became a corporate slave, and for four months I had nothing in mind but bills, money, credit cards, insurance, and loans.

During that 4-month summer, I had never seen my college friends. I had to decline whenever they invited me out as I was either at work or sleeping. Instead, I hung out with my co-workers who were mostly in their late twenties to forties. I was the youngest in our group.

So I was in utmost shock, on the first day of my junior year. I stepped through the university gates and I immediately felt it: The murmurs, voices, and expressions vibrated and bounced on the walls and the grounds. The laughs and cheers and hugs and jeers happening all around me—they all felt… so young. It was a far cry from the tired, drone of voices back at work.

The pines swayed, the beetles sang. The north-easterly Amihan slid down the mountains, glacial and fresh under the fading summer sun. I felt immensely grateful. I had just turned 19 at the time. I almost couldn’t believe it. I belong! In this frenzy of youthful exuberance, I belong! I’m still young, thank God!

That wave of juvenile energy made me acutely aware that something inside me has changed. It was like waking up in the middle of the night, suddenly cold and freezing, to find that the bonfire has been smothered.

Surrounded by pure, unrestrained laughs and unburdened exclamations, I realized that the frigid waters of adult skepticism and resignation have seeped through my soul—and I didn’t even know it.

I expected things to be difficult. My job and classes alone took 15 hours of my day while the rest is spent on group productions (rehearsals, writing, shooting, editing), commute, and miscellaneous stuff. I thought I could survive with three hours of sleep on regular days, and maybe a few hours more during day-offs.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, I spent all 24-hours with work, school requirements, and a bit of class. I say “a bit” because I maximized the absence cap of each class. I absented myself as many times as can be officially allowed, and as many more as an instructor’s sympathy would tolerate. I lived on 30 to 40-minute naps on my jeepney commute or during the classes, I managed to attend. I crammed a few more winks during day-offs if we didn’t have production practice or shooting projects.

I survived that year’s first semester, but it took an obvious toll with the drop of my grades. I didn’t care much about it, but I often had above-average grades before junior year. I even managed to join the “Dean’s List” of top graders once. For that semester, however, my grades were just high enough to keep my scholarship.

We have internships in the second semester, so I planned to quit my job then. But my father suddenly suffered a stroke. The hospital bills and the worrying possibility that my father might not be able to drive jeepneys anymore scared me into keeping my employment. I have three younger siblings. I couldn’t even afford to grieve if the worst happened. I had to keep the job, just in case.

With the internship added to the fray, I started maximizing my absence cap at work as well. I called in sick as much as my manager would permit. I was absent for months in classes where the instructor isn’t strict with attendance. Some sympathetic instructors even let me not attend classes altogether, as long as I submitted my requirements.

That semester, I failed four of my six classes, failed my internship, lost my scholarship, and lost a potential promotion at work with all my absences. Thankfully, my father did recover and slowly but gradually resumed working.

There is one moment that constantly plays in my mind, whenever I remember those times. Nothing very special, but I recall it vividly for some reason.

My mom asked me to buy groceries while she watched my dad at the hospital. I withdrew my piddling pay, shrunken with all my absences. I bought the items, went to the hospital, accompanied my mom for a bit, and then left for work.

I remember it was a cloudy afternoon when I exited the hospital. Maybe it’s the rare, worried expression on my mother’s face. Maybe I was exhausted, fatigued from the never-ending grind. Maybe it’s the self-pity welling in my heart, which I tried to swallow because I have neither time nor money to deal with it. But as I trudged towards the hospital gate, I felt some stuffiness in my nose and a lump in my throat.

I thought of Kyu Sakamoto’s Ue o Muite Aruko (“I look up when I walk”). The song tells the story of a man who looks up and whistles while he walks so that his tears will not fall. Being in a public place, I tried doing the same. I can’t whistle though, so I contented myself with a whistling rendition of the melody in my head.

As if on cue, light droplets started to fall from the sky. The drizzle quickly turned into rain, wetting my forehead, and the rest of my face. I went to work soaked, but comfortable, my pain concealed from unwelcome eyes.

I could have quit after 4 months of work. I could have just taken a part-time job. Maybe things would’ve worked out, even without an above-minimum pay. But more than the addiction to a salary and the necessities that followed my situation, I guess what I really wanted was to feel like a financially capable adult. I wanted to be like those adults in the movies who can afford to eat at a restaurant, seemingly any restaurant regardless of price, when they’re hungry. Those adults who plop down at a coffee shop or bar when they’re feeling sad or smoke a cigarette from their balconies while gazing at the skyline in melancholy. I longed to stand in a tile-floored shower, like they do so often in dramatic scenes, and feel the hot-and-cold water wash the stress away.

I grew up in a house without balconies, without tiled bathrooms nor hot and cold showers. I don’t go to coffee shops because I can’t afford to spend more than ten pesos for coffee. And I go to cheap restaurants only during very special occasions; Never casually, out of craving or mood. My luxury, as a child, was McDonald’s regular burger with fries and soda. Don’t mention an up-size, much less the Big Mac. They’re too expensive for me.

In the company of my older, more worldly, and well-off co-workers, I found myself dreaming of condos, cars, and beach vacations. Maybe a Big Mac or two, without feeling guilty for “spending too much.”

But while I was focused on getting paid with a job, I would learn, from a chance encounter with old friends, that someone who used to make a film project with me has won a national award for his new short film. Another friend has gained recognition from major news outlets for her work in community journalism. And my debate club friends were winning “higher rounds” in national competitions.

My peers are growing and flourishing in their fields of passion, while here I am, grinding hour after hour to get my bi-monthly pay—for what? I’m missing out on the prime experiences of my youth, for what? A car? A condo? A safety net to ensure that, should the worse happen to my dad, I can at least keep living this cycle of deprived sleep and money chasing? I’m trading nearly 12 months of my life, for a quarterly two-nights-and-three-days beach escapade?

Of course, these successful friends of mine are naturally better off: Their allowance rivals my daily pay, they have cars, their houses have tiled bathrooms, hot-and-cold showers, and wide balconies. With their privilege, they’ll naturally get ahead. But regardless, I don’t want to spend my time, time that my privileged friends and I both have—this precious, irreplaceable time of my youth—on menial work that neither grows my skills nor nourishes my soul.

The drizzle outside the commuter jeepney has stopped. I look at the clear, shiny droplets of water trickling through the windowpane, the city sparkling and iridescent. Summer has just ended, and my junior year passed along with it. The door to my left opens and the jeepney driver hops in, plugs the key, and starts the vehicle. The jeepney hums and shakes away the thin, surrounding fog.

It’s time to go.

I get home, open my laptop, and type a letter to my manager. The new semester starts next month. I have a lot of catching up to do.

***

I first wrote this piece in the middle of 2015. I was freshly resigned. From Up on Poppy Hill is still my second-favorite Studio Ghibli film, just below Spirited Away.

The Film: From Up On Poppy Hill, directed by Goro Miyazaki (Studio Ghibli)

*DO watch the original Japanese movie version (with subtitles). DON’T watch the Japanese-language trailer. It has spoilers. The US-release trailer is better.

The Song: Ue o Muite Arukou by Kyu Sakamoto